This article originally appeared on The Ruggist on 13 February 2016 C.E. under the same title. On 23 June 2018 C.E. it was re-edited and updated to correct minor name and content changes as well as to provide better quality images.

A wise man would have been prescient enough to have completed this article in time to have published on 2 February 2016, and then, à la façon the wonderfully annoying film ‘Groundhog’s Day’ further belaboured you with yet another long winded diatribe in support of copyright via a now second mention of that film. ‘We won’t find out until we grow…’ to quote that film’s use of the iconic song ‘I Got You babe’. Discussion of my relative wisdom notwithstanding, such an opportunistic article was not meant to be for a great conundrum had beleaguered me since shortly after the publication of my last missive on copyright in the rug and carpet industry entitled ‘No Euphemisms, It’s a Knockoff!‘ Only in recent weeks has an acceptable solution presented itself and so, without further adieu, I offer a footnote of sorts on copyright in general, and of course what that means to the rug industry. Apologies in advance for the somewhat tedious and essay like nature of this article; I trust those of you who care about more than just to paying lip service to copyright will find it most intriguing. Enjoy!

‘Only one thing is impossible for God: to find any sense in any copyright law on the planet.’ – Mark Twain’s Notebook, 1902-1903

The first real copyright law was the British Statute of Anne (also known as the Copyright Act 1709) under which, copyright was for the first time vested in authors rather than publishers and so (along with other changes taking place in society) began the notion that commodified human knowledge was individually owned rather than collectively, at least for the fourteen (14) year term length of the first copyright law. This proved to be a ‘watershed event in Anglo-American copyright history… transforming what had been the publishers’ private law copyright into a public law grant’1; one that has influenced every piece of copyright law since and still to this day in the 21st Century is ‘frequently invoked by modern judges and academics as embodying the utilitarian underpinnings of copyright law.’ But what in God’s name (or not) does this have to do with rugs and carpets? I know, it’s really tedious isn’t it? Stay with me.

‘We have a massive system to regulate creativity. A massive system of lawyers regulating creativity as copyright law has expanded in unrecognizable forms, going from a regulation of publishing to a regulation of copying.’ – Lawrence Lessig

Somewhere in the intervening years between 1709, the ratification of the United States’ Constitution in 1788, the British Copyright Act of 1842, the Berne Convention of 1886, the United States’ Copyright act of 1976, and the United States joining the Berne Convention in 1989 the idea of protecting creators has gone horribly wrong. Best expressed by the ever so intentionally imprecise language of the United States’ Constitution, the grant of copyright is intended to ‘promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts’ by providing creators ‘exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries’ for, and here is the important part, ‘limited Times’. In the United States this was originally fourteen (14) years, later changed to twenty-eight (28) – with option to renew, and then through a series of convoluted engagements with the courts, congress, and incessant lobbying by corporate interests is now an astonishing life of the creator plus seventy (70) years. This has the potential to restrict the use of created material, a ‘lock’ of sorts for, lets be extremely generous but not unreasonable and still within the confines of possibility, and say one-hundred sixty (160) years.2 That is certainly a long way from fourteen (14) and is definitely an unreasonable stretch of the imagination to call it ‘limited’. Unless of course you’re a geologist, but we aren’t.

‘Up until the final decade of the nineteenth century, the United States and the United Kingdom did not recognize copyright in each other’s creative works.’ – Matthew Pearl

Of course many people don’t live in the United Kingdom nor the United States, but by way of the aforementioned laws and conventions and a veritable laundry list of other treaties and conventions including the World Trade Organization’s ‘Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights‘ which requires all WTO member states (162 of 196 countries worldwide) including those not members of the Berne Convention to accept almost all of the conditions of the Berne Convention, the copyright law of the land is all but homogenized across the globe. In short (and I know this is way too late) copyright is at minimum: life of the creator plus fifty (50) years for most of the world. Some countries are even more bold than the United States and extend it to life plus one-hundred (100) years (I’m talking about you Mexico). Hahaha! Hahaha! Hahahahha! Hahahha. No seriously, this is actually laughable it is so thick with irony. Why you ask? I thought you never would.

The prompt for this final (Shall I laugh again?) installment on copyright was an email I received shortly after the publication of my last piece on copyright. It suggested The Ruggist would be able to do well for himself by continuously shaming so called copyists and in exchange, charging a fee. That is not who The Ruggist is, nor is it what The Ruggist is about, so I politely said as much, just as I have here and left it at that. The letter however did prompt me to examine the issue of copyright very closely, and now implores me to address the large elephant in the room.

‘I’m a bit cynical that it ever will be addressed properly. I think it is healthy to get some sort of copyright protection. But some of it has gone on forever.’ – Peter Gabriel

The sum of our human experience has brought us to where we are today, both big picture and within the cute and cozy confines of our beautiful world of rugs and carpets. We borrow, we are inspired, we copy, we improve, and we do this from a wide range of sources past and present. We now also do this hypocritically. Because of our ever evolving laws we have been continually extending the term of copyright except for works created before 1923. Those are generally regarded as public domain; anyone can use them. Moreover, I would argue that not only are we ‘free to use them’ as is commonly said, but we are entitled to use them as the now collective owners of the previously privately owned work. I can use it, you can use it, anyone can use.

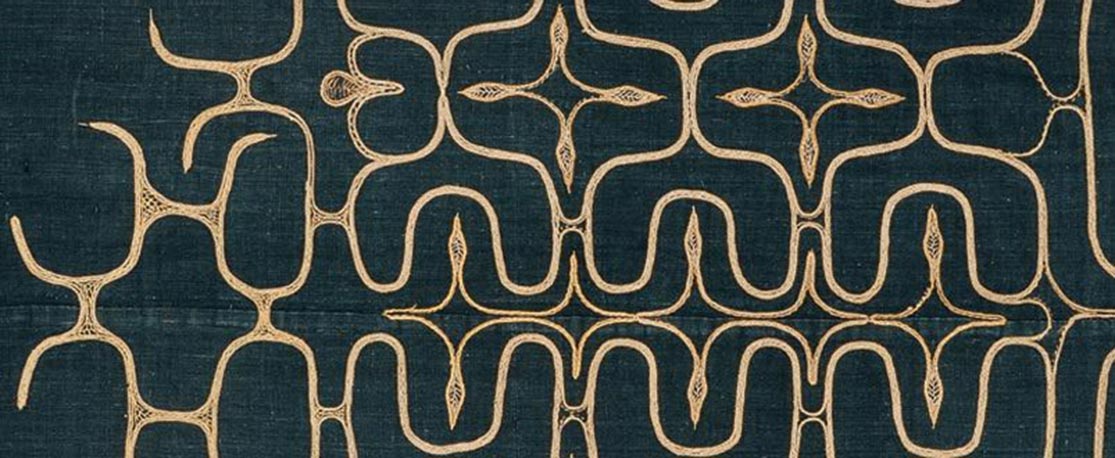

Take for example the above image of a textile fragment attributed to the indigenous Ainu people of Japan. The Ainu people no longer exist as a distinct ethnic group, and due to the aforementioned laws and treaties (of which I can assure you the Ainu could not have cared less about even if they had known of their existence) these textile designs are now public domain, that is, we all own them.

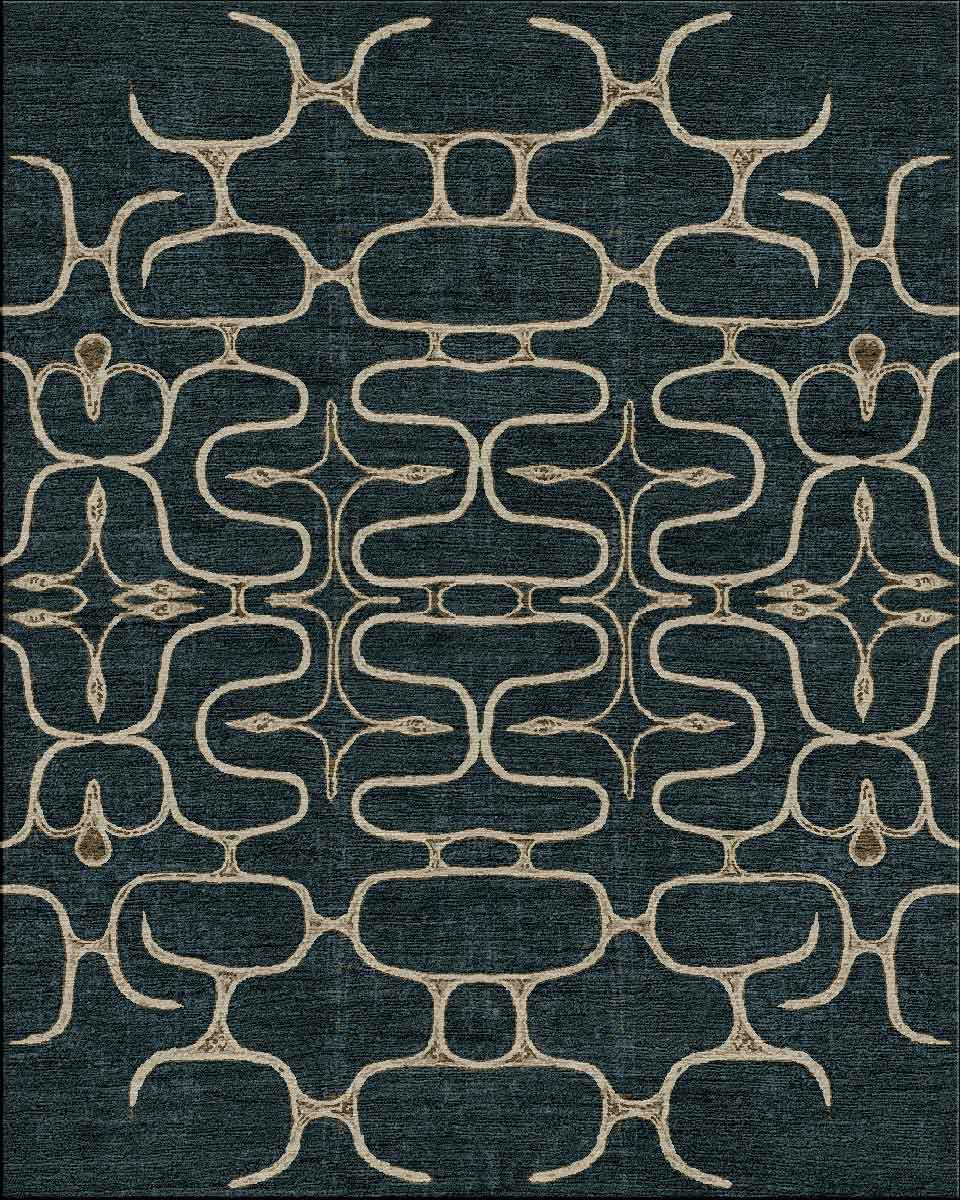

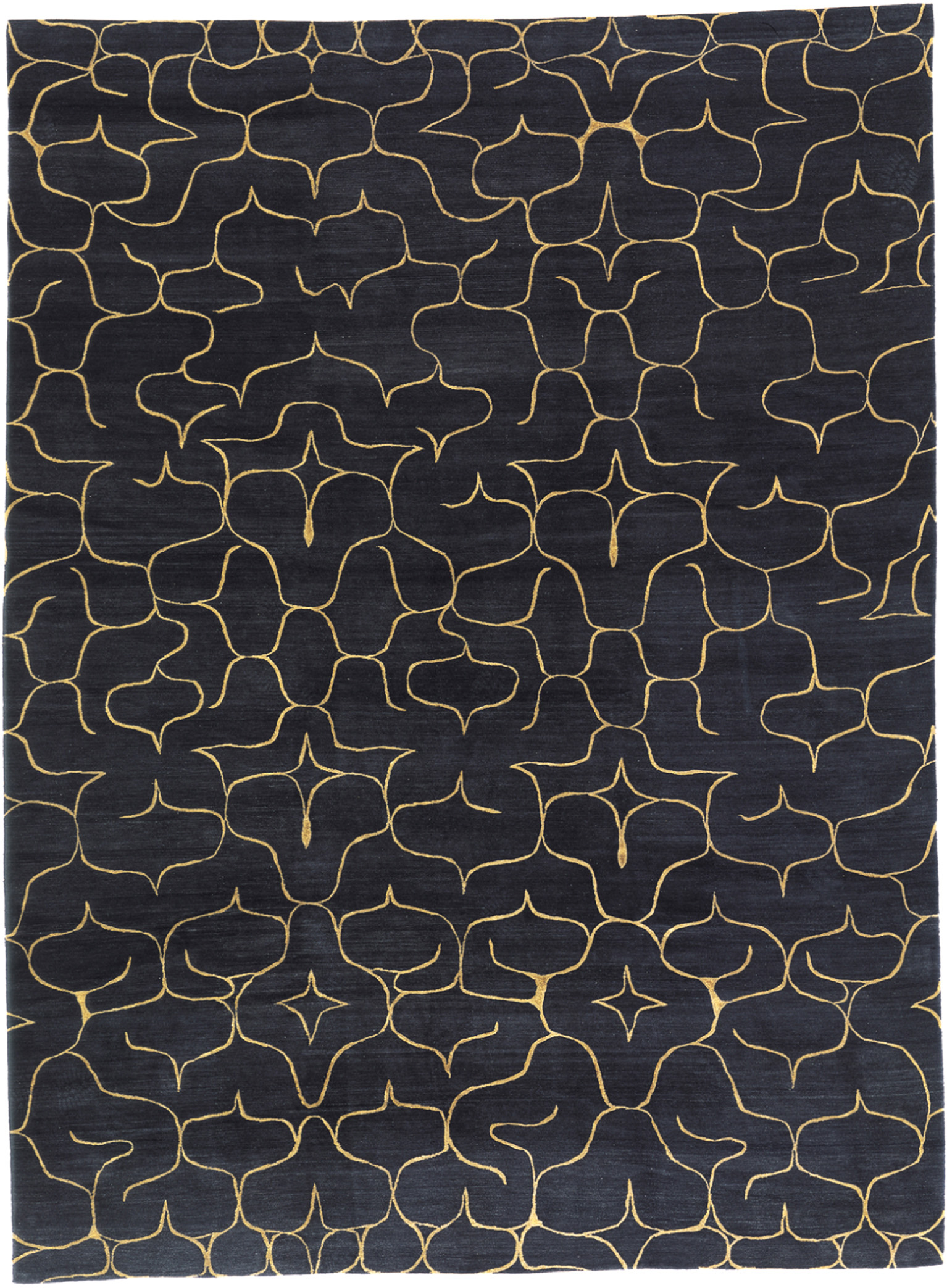

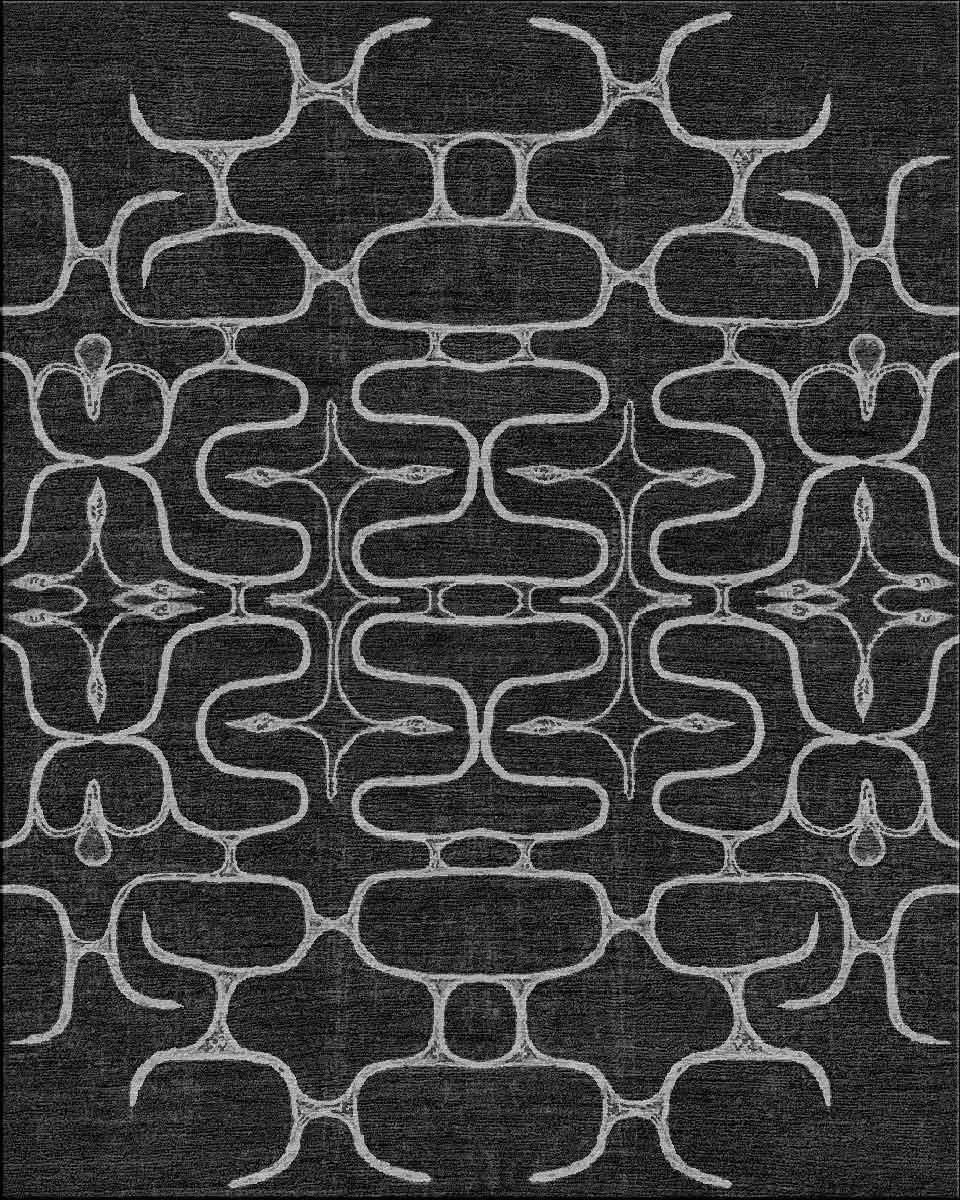

The similarities to the above carpet design are striking, and in fact it is ‘pretty literal and not a copy of anyone else’s design, other than that of the Ainu people’ according to Robin Gray who was inspired to create the rug design from the earlier work. And she is more than entitled to as one of the collective owners of that original. In fact any or all of us can make this very same design, that’s how public domain works. Moreover, anyone or everyone is entitled to make derivate works from the same inspiration such as the aforementioned fabric remnant from the Ainu people. Odegard Carpets, under the then leadership of Stephanie Odegard, previously had and while the designs are similar, perhaps even mistakable to the ‘ordinary’ or ‘casual’ observer, they are not infringing upon one another for the various reasons detailed herein and throughout The Ruggist’s series on copyright.

[wc_row]

[wc_column size=”one-half” position=”first”]

[/wc_column]

[wc_column size=”one-half” position=”last”]

[/wc_column]

[/wc_row]

The caveat of course is that ‘exact reproductions of public domain artworks are not protected by copyright.’ at least according to a landmark 1999 federal district court ruling, The Bridgeman Art Library, Ltd., Plaintiff v. Corel Corporation. This means anyone can reproduce a public domain work, but they may not assert any copyright claim over their work, unless…

‘You grow great crops in great soil. And the soil is the commons. Increasingly, we have monopolistic companies that try to take as much as they can for themselves. And we have a patent and copyright regime that makes sure that nothing goes back into the commons unless by an extraordinary act of generosity. This is not fertile soil for innovation.’ – Tim O’Reilly

Unless the new work being created is transformative or adaptive or whatever word you would like to use. That is to say it takes elements of the original, modifies it, changes it, rescales it, so on and so forth potentially ad infinitum until the original is potentially still apparent but the work is significantly different enough as to qualify as new; then copyright claim can be attached to the new work. This is the crux of the vast majority of contemporary rug and carpet production that asserts a claim of copyright. Inspiration was taken from a public domain source (or from a source from which no copyright ever existed e.g. nature), adapted, and then voila, something new. This newfound work is thusly protected under current Copyright law, which also grants the owners ‘… exclusive right to produce derivative works based on their original, copyrighted works.’3 Which begs the question, what is a ‘derivative work’? From the United States Copyright Office’s Flyer ‘Copyright in Derivative Works and Compilations‘ [Caution: Link is PDF], one of the zillion examples of things that may be derivative is: ‘A drawing based on a photograph.’ Is a rug or carpet based on a textile logically the same? It may be to use the same intentionally vague language subject to interpretation. If we allow such a distinction, the work of Robin Gray could be considered derivative as it changes medium, or we could group all textiles together and simply call it a copy. In the former Robin may be able to assert new claim of copyright, whereas in the latter she cannot. In this case (and properly) I’m erring on she cannot.

‘The problem with copyright enforcement is that when the parameters aren’t incredibly well defined, it means big corporations, who have deeper pockets and better lawyers, can bully people.’ – Shepard Fairey

‘Technically, you cannot really own a book you bought; you can only own the sheets of paper your copy is printed on; unless, of course, you are the book’s publisher.’ – Mokokoma Mokhonoana, The Selfish Genie: A Satirical Essay on Altruism

But what if a designer, in this case one Michael Christie, takes a public domain design from a turn of the former century brass doorknob and with various changes and additions adapts it as a rug design? He, that is I, now have a new design fully protected by modern copyright law, until I die, plus, in my case under Canadian law another fifty (50) years. Assuming I live to say eighty-five (85), I welcome you to start making ‘derivative work’ – because that’s all adaptation really is – in 2111. Yup, in ninety-five (95) years you can start using my work.4 Imagine however if I was younger, and lived longer as I mentioned at the outset of this article? In theory, had a twenty (20) year old American me designed it, who then lived to be one-hundred (100), you would be welcome to start using that design in 2166. How is it under current law we find it perfectly acceptable to dictate that no one other than the copyright holder (their heirs or assigns – as if they did any work) may use the design, and moreover create derivative work thereof, one-hundred fifty (150) years into the future, when the inspiration from which it was adapted, err, derived is only say one-hundred sixteen (116) years old? The answer is hypocrisy, extreme arrogance, naiveté, and a penchant for irony best summed up by the phrase ‘I’ve got mine, now screw you.’

‘Posthumous retention of copyright is really a gangrenous foot-in-the-door for the coming zombie apocalypse. And who in tarnation really wants that?’ – Pansy Schneider-Horst

Furthermore my adaptation from this doorknob and my subsequent copyright of the new design do not in anyway give me claim over the original work. Everyone else is still free to create derivative work from it, and so long as it is adapted differently than mine, they too are free to assert copyright over their work and there is nothing I can do about it. Again, that is how public domain works. From the United States’ Copyright Act of 1976, ‘In no case does copyright protection for an original work of authorship extend to any idea, procedure, process, system, method of operation, concept, principle, or discovery, regardless of the form in which it is described, explained, illustrated, or embodied in such work. That is to say the ‘expression’ of the idea is protected, but not the ‘idea’ itself.’ This is why anyone can make a carpet in the style of Jan Kath’s ‘Erased Heritage’, for example, so long as they do not duplicate the work. This is a distinction many, not just in the rug industry, would rather not accept.

‘If I’m seeing you, you’re going to influence me. I’m sorry – I’m just that way. I’m a big sponge. You can’t copyright an aesthetic.’ – Douglas Carter Beane

‘Unfortunately, some textile companies attempt to embellish the purpose of copyright law by claiming it grants (anyone willing to fight) the right to common, unprotected design elements, often found in the public domain.’ and ‘Further, the current law provides too much copyright protection for anyone who registers even the most basic textile design. As a result, certain textile design companies, often referred to as ‘trolls,’ enforce copyrights and make litigation a significant revenue stream since many defendants don’t have the money or desire to defend cases, and the cost of settling is often cheaper than taking a case to trial.’5

‘Of course people are going to copy and be inspired. If work wasn’t inspiring then it wouldn’t be successful.’ – Peter Kitchen

In the grand and nobel quest to protect those in our society who create we fashioned the notion of copyright, originally and arbitrarily ascribing a limited term of fourteen (14) years. We now have a situation in which we assert claim to a term far in excess of one-hundred (100) years while simultaneously still looking into the past for inspiration, often well within the timeframe we so foolishly seek to assert over our own claim. It is horribly arrogant to assume we can control that distant a future, and quite frankly it restricts rather than ‘promote[s] the Progress of Science and useful Arts’. For what motivation exists to innovate with new work if in its stead a creator may routinely rest upon their laurels espousing ‘This is my work! You may not be inspired’ as if they had miraculously conjured their design from the ‘primordial ooze‘ never having been inspired. Bullocks!

Each iteration, each generation must copy, learn, adapt, et cetera from the prior for that is how we have arrived here, and it is how you are able to read these words. We must be tacitly aware that copying, being inspired, deriving, however you would like to massage this semantically is part of our human nature and growth. Attempting to delay that progress by enacting a prohibition on copying such that someone born today may not ever in their lifetime be able to legally use source material to create a derivative (or inspired if you’d rather) work is woefully destined for failure.

‘There’s nothing you can find that cannot be found.’ – Wicked Little Town (Tommy Gnosis Version), Headwig and the Angry Inch.

Length of copyright is just one of the myriad of issues that must be addressed including, but undoubtably not limited to, what happens when two (2) creators take inspiration from the same public domain source and create designs that are strikingly similar if not almost identical. Who has the rights to that? I have some thoughts, but will spare you another tedious diatribe. Unless you ask.

‘Unfortunately it is not possible for a designer to search Copyright Office records to see which designs have been previously registered. Consequently, legitimate designers with no intent to copy are being hit with infringement lawsuits since they have no way of knowing that others have claimed similar designs as their own brainchild.’5

I am in no way arguing for the abolition of copyright, but the current system is no longer serving those it was meant to protect – that is creators – and must be reformed. I believe a term limit of one (1) generation, say an absolute length of twenty-one (21) years is more than sufficient to allow for both the ability of a creator to profit from his or her work, and for society to progress without the burden(s) imposed by our current system. This would force creators to continue to create and would hedge against a corporate monopolistic state that seeks to restrict ownership of what is our collective knowledge. Does this sound radical? Socialistic? Perhaps, but it should not. Ask yourself as a creator: What good will you receive from your work forty-five years after your death?

Brief afterword [Added 14 February 2016]: An early reader of this post told me: ‘It’s all a bit convoluted and tedious, the legislation, etc.’ I could not agree more and so is copyright law. How are any of us, including Lawyers I might add, supposed to know what we can and cannot do when the legislation is ‘convoluted and tedious’ and it’s all but impossible to agree on what any of this means? Ignorance of the law may be no defence, but the inability to fully understand it… Thank you for reading and thank you for thinking about what copyright means to our industry. +The Ruggist would like to thank everyone who discussed this issue with him, including my weary dinner companions Sunday night during DOMOTEX who had to endure a small rant. As one of them said ‘Part of the problem is the complexity of the laws it is not?’

Footnotes:

1 – [Page 916 of Patterson, L. Ray; Joyce, Craig (2003). ‘Copyright in 1791: An Essay Concerning the Founders’ View of Copyright Power Granted to Congress in Article 1. Section 8, Clause 8 of the U.S. Constitution’]

2 – This assumes a far fetched scenario in which a person creates a copyrightable work at age twenty (20) and lives to an age of one-hundred ten (110).

3 – According to Stephanie Morrow, Professor of Media and Communication at Temple University

4 – Age at death, 85 in the year 2110. Copyright expends to the end of the year of death. Thus 2111-2016=95

5 – Jeffrey A. Kobulnick, Partner at the law firm Brutzkus Gubner.